The U.S. Constitution was designed to promote interstate commerce, but Congress acted in 1945 to artificially fragment insurance markets state by state. As a result, individuals can buy health plans only from insurers that are licensed by the state where they live. Without any competition from companies based outside their state, the result is higher premiums on the individual market—and premiums that vary greatly from state to state, with large disparities consistently tracking state borders. This is in sharp contrast with the premiums for employer-sponsored plans—which are exempt from state regulation and vary little between states.

In addition to restricting competition, state regulations have long increased the cost of health insurance through benefit mandates and restrictions on cost controls, but many of these regulations have been mandated nationwide by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Yet ACA is also responsible for an increase in the variation of individual market premiums between states, as well as a general increase in premiums. It has done so by requiring insurers to price coverage according to the idiosyncratic balance of medical risks of those who happen to be enrolled in the state, rather than in proportion to individuals’ own expected medical costs. This means that insurers in states with a relatively sicker pool of enrollees must price ACA plans much higher than plans in states with a relatively healthier pool of individuals.

Reformers have long urged that individuals be allowed to buy health insurance across state lines. Unfortunately, the precarious financing of state individual-market risk pools, as structured by ACA, is inherently incompatible with vigorous interstate competition. However, the large economies of scale associated with many health-care services make competition across state lines essential to the efficient provision of medical care. Such competition will require reestablishing an individual insurance market outside ACA’s regulatory framework.

The U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3) was designed to prevent states from restricting trade and competition across their borders with protectionist legislation.[1] Over time, a unified national marketplace has, in most industries, allowed American businesses to grow nationwide, to benefit from associated economies of scale, and—through competition—to pass those gains on to consumers.

Yet after the Supreme Court ruled in 1944 (United States v. South Eastern Underwriters Association) that the Sherman Antitrust Act applied to insurance, the industry pressured Congress to overturn the ruling.[2] This led to the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, which put the states in charge of regulating insurance, including the exclusive power to license insurers to operate within their borders; the new law also protected state insurance regulations from preemption by federal regulation.

As the proportion of Americans with private health insurance soared from 23% in 1945 to 83% in 1975, the industry grew up fragmented into 50 different states.[3] The inconvenience of this arrangement was, to some extent, checked by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, which preempted state regulation of health-care benefits for self-insured employer plans.[4] (A self-insured plan is one where the employer pays the benefits that it offers from its own funds but typically hires an insurance company to administer the benefits.) Though this provision allows large employers to procure health-care services for their employees nationwide, the millions of Americans who must get health-insurance coverage from small group plans or individual policies remain locked out of health plans from other states.

The Republican Party’s 2000 platform pledged to permit small businesses to “band together, across state lines, to purchase insurance through association health plans.”[5] In 2008, 2012, and 2016, this proposal was expanded to allow individuals to purchase health insurance across state lines.[6] And in 2018, the Trump administration finalized a regulation to facilitate the formation of Association Health Plans for small businesses.[7]

The following year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a formal Request for Information with the intent of making it easier for individuals to purchase insurance across state lines but was unable to make any progress in implementing it.[8] The upshot is that allowing individuals to purchase health insurance from other states would likely require statutory authorization and revisions to the McCarran-Ferguson Act.

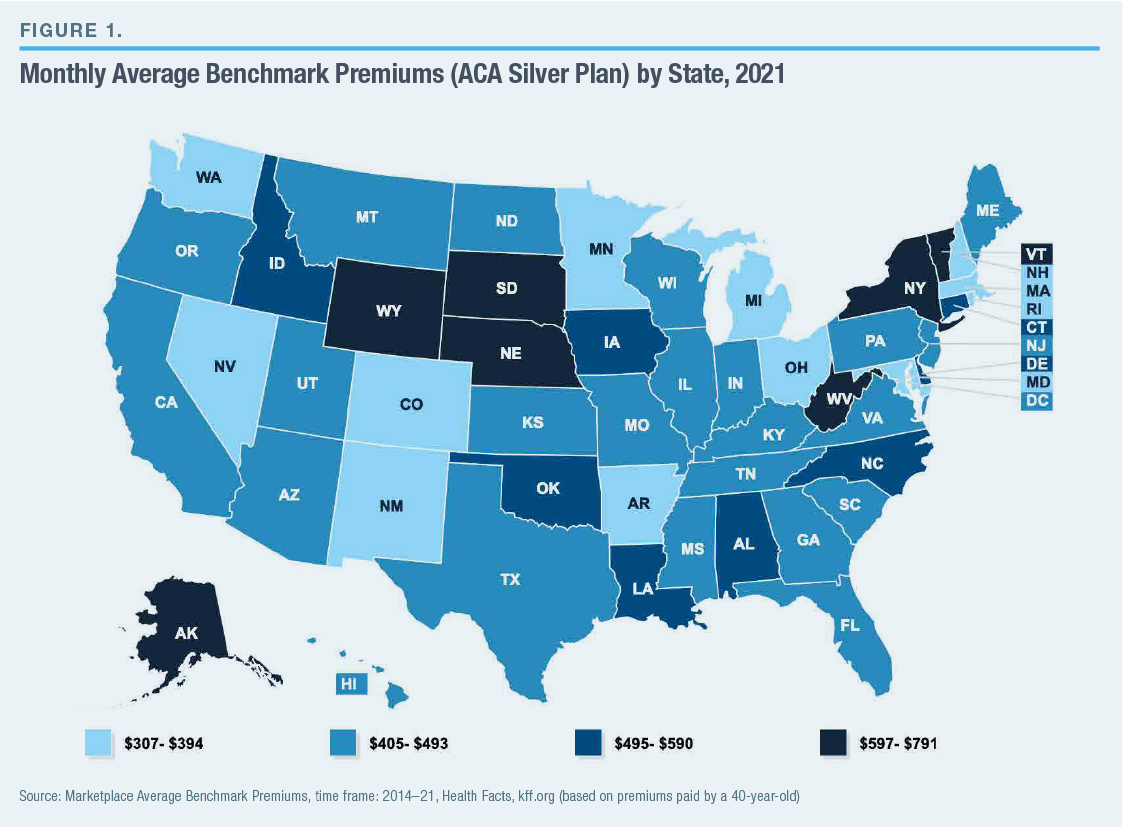

Premiums for equivalent ACA plans on the individual market vary greatly between states. Average premiums for benchmark silver plans in 2021 range from $307 per month in Minnesota to $791 in Wyoming (Figure 1). Americans can therefore find themselves paying very different prices for a product that is standardized by federal law.

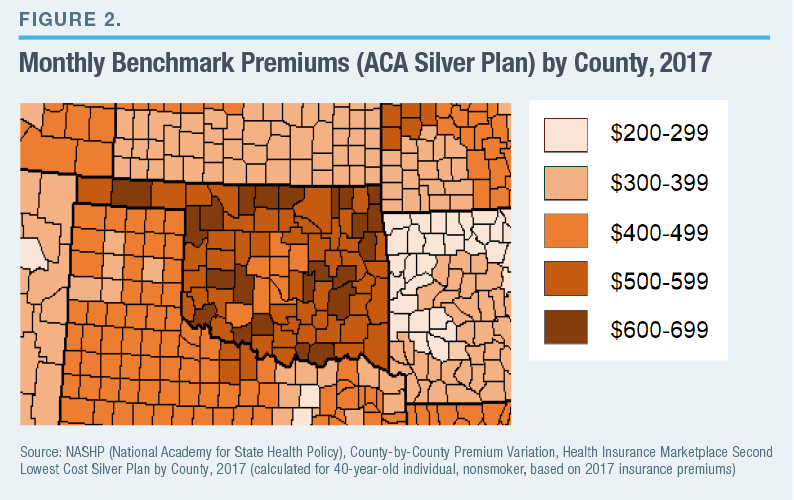

The variation in individual market premiums does not simply reflect differences in the underlying cost of delivering medical care; it shows state-specific differences in health-insurance markets. This is clear from the fact that, while premiums vary relatively little within states (even across substantial distances), substantial differences in premiums track state boundaries (even between neighboring counties). For instance, in every county in eastern Oklahoma, benchmark premiums range from $500 to $699, whereas every county across the border in western Arkansas has premiums between $200 and $399 (Figure 2).

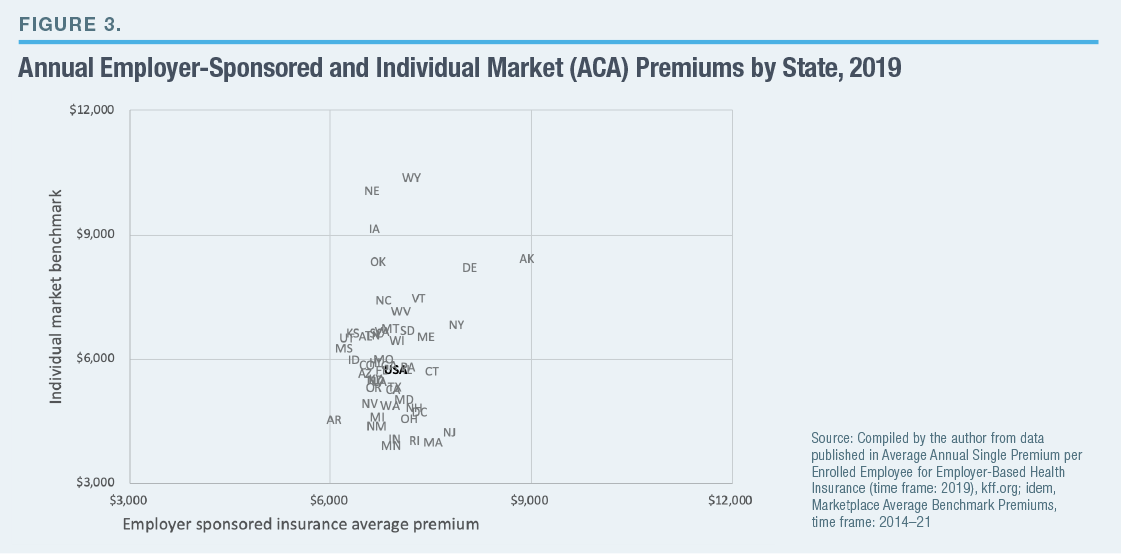

Under ERISA, large employers typically manage the health benefits covered by their self-insured plans across state lines, which frees them from restrictive and potentially costly state regulations. Employer-sponsored health-insurance premiums are not just lower on average than those for equivalent individual market plans but vary much less between states (Figure 3).

State governments often operate with limited administrative and technical resources and are highly vulnerable to lobbying by interest groups. Medical providers—physicians and hospitals—are well represented in state capitols, and they frequently push legislatures to mandate that insurers pay for services that they provide, as a way to increase the sales (and prices) of these services.

The typical state had fewer than one benefit mandate in 1970; by 2017, the average was 37. James Bailey of Temple University has estimated that each benefit mandate enacted by states tends to increase health-insurance premiums by 0.4%–1.1% and that new mandates were responsible for 9%–23% of premium increases during 1996–2011. Benefit mandates may have added value to insurance coverage by preventing insurers from leaving gaps in coverage, in order to deter sicker individuals from enrolling.[9] Still, in a study of the period 1989–94, Frank Sloan and Christopher Conover of Duke University estimated that 20%–25% of Americans without health insurance were deterred from purchasing coverage because of the added costs resulting from benefit mandates.[10]

Lobbyists for hospitals and physicians have similarly pushed states to enact laws that increase their pricing power, by making it hard for insurers to exclude them from networks of covered providers. When HMOs began to squeeze hospital costs in the late 1990s, more than 1,000 bills were introduced in state legislatures. Most states enacted laws requiring insurers to reimburse “any willing provider” for treatment according to their standard payment arrangements. A study by Maxim Pinkovskiy of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that anti-HMO state laws drove up the incomes of medical providers, increased service use, slowed reduction in hospital lengths of stay, and caused U.S. health-care spending to increase by 2% of GDP—accounting for much of the growth in health-insurance costs in the early 2000s.[11]

The structure of insurance markets does much to influence the ability of providers to inflate and pass on costs. Blue Cross hospital insurance plans were initially established by the American Hospital Association (AHA) for the sake of bolstering hospital revenues, and AHA in most states secured favorable tax and regulatory policies to protect hospitals from competition.[12] By providing open-ended reimbursements to facilities according to the expenditures they incurred, such insurance plans caused hospital costs to soar.

If individuals were allowed to purchase plans from other states, regulators in each state would be forced to place the interests of these individuals above those of insurers and the rest of the health-care industry. A 2008 study by the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that the reduction in premiums resulting from allowing individuals to shop for insurance across state lines could reduce the number of uninsured Americans by 12 million.[13]

Section 1333 of ACA allows states to combine their markets, enabling residents to purchase plans from other states. But ACA also eliminated much of the variation in state-level regulatory arrangements, by requiring all states to adopt many of the costliest benefit mandates and plan design features that had previously existed at the state level.

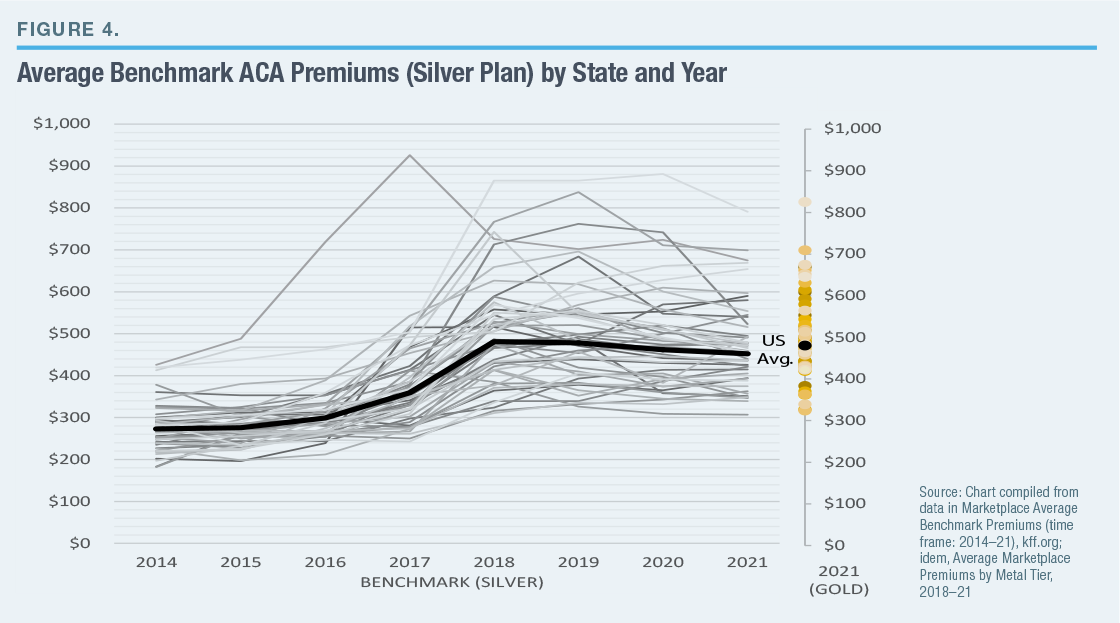

In fact, much of the present variation in premiums between states is the result of new market distortions introduced by ACA, rather than features that preceded it. Indeed, the dispersion of premiums between states has increased greatly since ACA was implemented in 2014 (Figure 4).

The spike and variation in premiums on the individual market since ACA went into effect are largely the result of the legislation’s “community rating” regulation, which requires insurers to cover all enrollees in broad demographic categories at the same premium, regardless of differences in their medical risks. This regulation led plans to prove disproportionately attractive to individuals with the most serious medical assistance needs—causing costs to soar and premiums to rise until few unsubsidized healthier enrollees remained.[14]

This arrangement created enormous uncertainty—requiring insurers to price plans without knowing the likely costs of covering those who enrolled. As a consequence, some insurers set premiums too low—incurring enormous losses while driving competitors from the market.[15] By 2018, 52% of Americans lived in counties that had only a single insurer offering plans on the individual market.[16] Though competitors have since returned, as the market has stabilized (only 10% of counties had a single insurer for 2021), it has so far done little to narrow disparities in premiums. Wyoming, which has the highest premiums in the nation, had only a single insurer on its individual market until 2021 and does not require regulatory approval of rate increases—leaving its insurer’s pricing power largely unconstrained.[17]

Nebraska, which has the nation’s second-highest premiums, similarly had a single insurer participating in the ACA exchange. It hiked premiums on the individual market to take advantage of an arrangement known as “silver-loading.”[18] Silver-loading was a response to the absence of federal appropriations for Cost-Sharing-Reduction subsidies, which expand the proportion of medical costs covered by silver plans from 70% to 73%, 87%, or 94%, depending on enrollees’ annual income. States realized that they could help insurers claim additional federal subsidies to make up the shortfall by allowing them to inflate benchmark plan premiums.[19] Yet while silver-loading has clearly artificially inflated silver-plan premiums, it does not explain the expanded variation between states, as the variation in premiums for gold plans (which cover 80% of medical costs) is just as great (Figure 4).

In an attempt to reduce premiums by increasing the proportion of enrollees who need little medical care, five states and the District of Columbia have reinstituted the individual mandate penalty that Congress repealed at the end of 2018.[20] Yet the mandate did little to compel individuals to enroll in order to reduce premiums at the federal level because the penalty was small relative to the often exorbitant cost of premiums, and its reestablishment at the state level is unlikely to be more effective.[21] Reinsurance programs that provide additional subsidies to plans that attract disproportionate numbers of sicker enrollees have been established by 15 states and may prove more successful at reducing premiums.[22] But the cost of such programs would soar if an influx of enrollees from other states were permitted.

The structure of the ACA-regulated individual market, which depends on a delicately balanced risk pool, maintained by a combination of state-managed subsidies and regulatory cross-subsidies between plans, is therefore likely to be incompatible with vigorous competition across state lines. Such competition is therefore likely to require the reestablishment of an insurance market where plans may be priced in proportion to individuals’ medical risks.

This market already exists, albeit to a limited and restricted degree, with Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance (STLDI). Such plans are available in about half the states, though the maximum duration of enrollment permitted by state law varies (some states allow plans to guarantee renewal for up to three years, while others limit enrollment to three months).[23] STLDI plans are able to offer significantly lower premiums and better benefits to individuals who sign up before they get sick, and they seek to attract enrollees by providing access to broad national networks of medical providers. ACA plans, by contrast, typically cover only the bare minimum number of local providers required by state law.[24] Allowing individuals to purchase STLDI plans from other states would make insurance coverage more affordable while also facilitating the development of competition between national networks of medical providers.

Congress should protect consumers by establishing national standards for STLDI plans. These standards should require insurers to renew coverage indefinitely, regardless of medical conditions that individuals may develop, and prevent states from forcing individuals to drop coverage that they purchased in other states.

Competition across state lines is necessary for any fundamental transformation in American health care. While the old model, providing services by local hospitals, made sense 80 years ago, the growing specialization of the medical profession and the capital intensity of surgical procedures make it increasingly inappropriate. Not every county can support cutting-edge neurosurgery, and some states may be unable to do so. Large academic medical centers and specialized facilities typically deliver significantly better-quality clinical outcomes than smaller hospitals, where staff may be poorly equipped and have little experience treating complex cases.[25]

Given that hospital care involves high fixed costs, economies of scale are substantial. In 2017, the cost of a knee replacement in the U.S. averaged $30,000, while that for heart bypass surgery was $78,000—but prices vary enormously between facilities.[26] At such levels, disparities in price and quality between facilities dwarf the cost and inconvenience associated with traveling to more efficient providers. Limiting individuals to instate insurance binds them to inefficient and often monopolistic provider markets that are often dominated by single medical systems—subjecting them to inflated pricing power and ever-rising costs of care.

The fragmentation of insurance markets by states also undermines the portability of health-insurance coverage between jobs. The inability to carry STLDI coverage across state lines prevents individuals from renewing plans. While some states prohibit the purchase of STLDI coverage altogether, moving to even the most pro-STLDI state would force individuals to purchase coverage afresh. This would expose them to the risk of coverage denials and rate increases due to preexisting conditions. A robust, competitive, private insurance market, therefore, requires the underwriting and interstate portability to go hand in hand. For insurance to be compatible with interstate competition, insurers need to be allowed to price it in proportion to an individual’s risks, and individuals must be allowed to retain insurance renewability guarantees as they move from state to state.

Christopher Pope is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Previously, he was director of policy research at West Health, a nonprofit medical research organization; health-policy fellow at the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce; and research manager at the American Enterprise Institute. Pope’s research focuses on healthcare payment policy, and he has recently published reports on hospital-market regulation, entitlement design, and insurance-market reform. His work has appeared in, among others, the Wall Street Journal, Health Affairs, US News and World Report, and Politico.

Pope holds a B.Sc. in government and economics from the London School of Economics and an M.A. and Ph.D. in political science from Washington University in St. Louis.